The Yukon River Quest: 715km of dehydration, hallucinations and days that never end

[device]

[/device][notdevice]

[/notdevice]

It’s been more than a week since we finished the Yukon River Quest and I still can’t feel one of my big toes. Apparently nerve damage is a standard result of paddling three days, three nights and 715km (444 miles) down a long, cold river in Canada. My toe should “thaw out” in a month or two, but I’ll have to wait another 12 months to experience the Yukon again.

And that’s the craziest thing about this race: despite going through a torturous test of sleep deprivation, dehydration and hallucinations, I have an overwhelming desire to do it all again. There’s something addictive about these ultras.

The Yukon River Quest is so much more than just a race, and therein lies its appeal. It’s part-race, part-adventure, part-journey into your own mind and beyond. It’s both marvelous and miserable, beautiful and boring, fascinating and fucking difficult. And it all takes place in one of the most breathtakingly-remote parts of the world you’re ever likely to visit.

The “Quest” – and that title is appropriate – begins long before the race itself. If you’re smart, you’ll spend months training and conditioning your body to withstand 50-70 hours of near-sleepless paddling. If you’re not, you’ll accept a last-minute spot in the event and blindly assume your mental stubbornness will get you through it. You can guess which category I fell into.

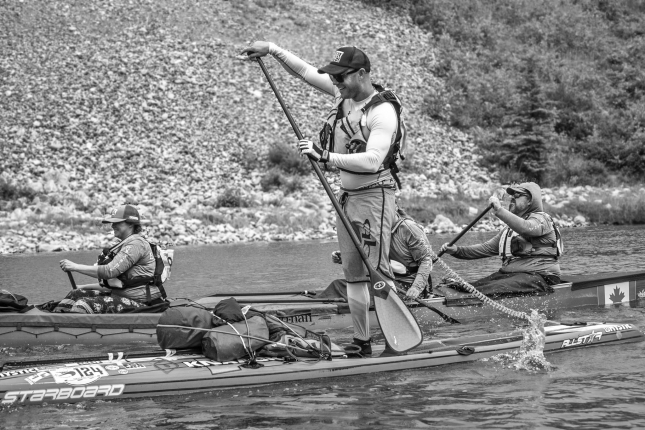

The vast beauty of the Yukon River (photo: @trev_sup/@paddleleague)

Even getting to the Yukon can be a mission. It’s in the north-west of Canada and a long flight from anywhere. The airport in the provincial capital of Whitehorse – population 25,000 – is so small you can walk straight off the street and up to the baggage carousel.

We arrived 48 hours before the start and immediately began preparing for something you can’t really prepare for. The tangible items – the board, the paddle, the safety gear and food – are easy enough, or they are if you have a local expert guiding you. Fortunately we’d teamed up with Stuart Knaack from SUP Yukon, one of the guys responsible for getting stand up paddling into this traditional canoe race a few years ago and undoubtedly the most knowledgeable paddler for a thousand miles in any direction.

Stu hooked me up with virtually all my gear – from water packs to life jackets to dry bags – as well as my board: the 14×27 Starboard All-Star. He also gave me priceless knowledge about how to read the river itself, which turned out to be one of the key pieces of the Yukon puzzle. Throw in the infinite wisdom of three-time champion Bart de Zwart plus the tireless work (and emotional support) of our media crew, Trevor and Kelli, and although I was entered in the solo division this was clearly going to be a team effort.

But I still failed my pre-race gear check. Twice.

24 hours before the race begins, competitors line up their equipment and get every single item ticked off by keen-eyed race officials. I tried to skimp on the clothing. We have to carry two extra sets plus an all-weather rain jacket. I don’t even own two sets of clothes let alone a heavy-duty jacket (light travel is my religion), so I ignored all advice and tried to save on space and weight. The officials were having none of it.

We also have to carry a tent, sleeping bag, foil blanket, boiler, waterproof matches, emergency medical kit and a big orange plastic bag. The bag was to mark your rescue point along the river if you quit and camped out in the bush, but it was also to be deployed as a pin if you found a body in the river. Apparently someone had gone missing downstream a few weeks earlier.

Gear check at the Yukon River Quest. I failed. Twice. (photo: @perfectnegatives/@paddleleague)

Around 11am Wednesday, an hour before our Quest began, it finally hit me.

I’d been so calm in the weeks leading up to the event. Too calm. The only thing I’d been worried about was the fact that I wasn’t worried about anything. But as I looked at the 116 other teams of SUPs, canoes and kayaks lined up on the river bank with their masses of gear and years of river knowledge, I realised we were in for one hell of an adventure.

You’d think a 715km race that spans three days would start at a slow, steady pace. You’d be wrong. The Yukon River Quest begins with a 400 metre dash down to the water’s edge, and this is where I made my first mistake.

I’m a good sprinter, at least on land, and despite every part of my brain telling my body not to do it (“Jog, you idiot.”) as soon as the horn blew I went full Usain Bolt and ran for glory. If I’d been first to the river I might have been able to justify this reckless waste of oxygen, but a few spritely canoe kids edged ahead of me and I had to settle for fifth (just to be clear: there’s no prize or even recognition for winning this part of the race, just ego).

The other reason it was a mistake, apart from being out of breath with 714.6km still to go, is that my gloves went flying out of my pocket during the run. My untrained hands were as soft as marshmallows and those gloves were going to be my savior. I’d spent hours researching them on Amazon. They were one of the few items I’d actually prepared in advance.

I managed to catch my left glove but the right-hander fell to the ground. It would have taken 10 seconds to stop and grab it, but the “Race to the Midnight Sun” had begun and I was caught up in the excitement.

So my hands were screwed before I’d even taken a stroke.

Run, Forrest! The start of the Yukon River Quest is a cruel, 400 metre sprint. (photo: @perfectnegatives/@paddleleague)

It’s hard to pick up your board when you’ve got 20-30kg of gear strapped to the front deck. Fortunately we met a helpful event volunteer (thanks, Chris from Calgary) who offered to stand in the cold river holding my board ready for a quick start. But because I’d signed up last, I had the worst spot on the river bank.

This race is meticulously organised, right down to your starting position. Sign up first and you get to place your craft farthest downstream. Sign up last and you’re already 200 metres behind.

Once on the water, Quickblade paddle in hand, I quickly realised the other stand up paddlers had actually trained for this event and that I’d be a fool to try to race them. I had to be smart and find my own rhythm or I’d be hitting the wall on day one.

Bart de Zwart and Brad Friesen were instantly out front given their advantageous board placement and immediately began extending the gap — Bart was so fast he was sitting third or fourth against the 100+ canoe and kayak teams for the opening few kilometres.

Peter Allen, third in the 2017 Quest, came charging past me around the 1km mark. Shauna Magowan soon followed and soon disappeared in front of me. I knew there were a few guys further back on inflatables, but my only lifeline on that endless first day was going to be the canoes.

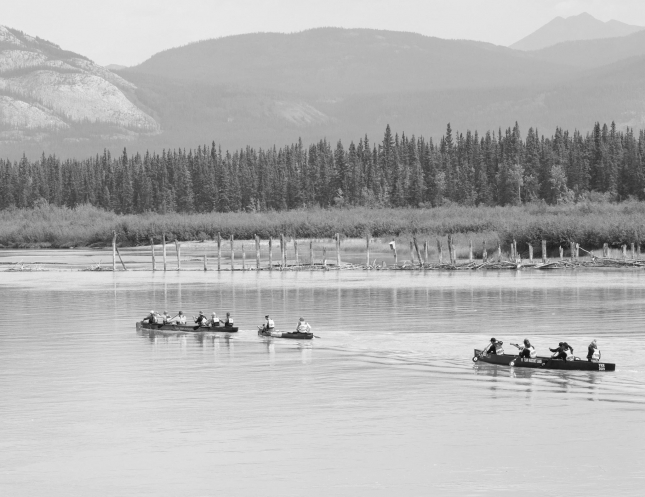

The Yukon River Quest is now 21 years old and this is only the fourth year SUPs have been invited. Apparently it was a big hurdle to get them on the start line in 2016: most of the race officials and fellow paddlers didn’t think stand ups had a chance of finishing but were soon proven wrong by the likes of Bart, Lina Augaitis, Norm Hann, Jason Bennett, Stu and the other pioneering class.

SUP is now very much accepted and welcomed but the majority of competitors are still sitting down, which creates a really cool atmosphere on the water. That’s especially true on the first day when everyone is relatively close together and you can chat with the passing canoe teams.

It was also a good thing for me because a four-person canoe creates a hell of a wash for drafting.

The four-person canoes became our best friends (photo: @trev_sup/@paddleleague)

The Yukon River Quest isn’t a race, it’s a story. It’s like a book that’s full of personality and “characters” that are trying to either help or hinder you.

Lake Laberge is one of those characters, though villain is perhaps a better term because this is where the water stops flowing and goes dead. The lake is a grind. It’s also 50km long and has its own unique weather patterns.

Bart had given me the motto of “Make the lake, make the race.” and therefore my only goal had been to make the cut-off time of 13 hours at the end of Lake Laberge. I’d cleared the first cut-off (four hours at Policeman’s Point, the lake’s entrance) with 30 minutes to spare and calculated I should be two hours safely inside the bubble by the time I got off the lake and back into the river.

Then the wind came up.

I suppose I jinxed us: I was paddling behind a two-man canoe and joking about how easy the lake was this year. It was sunny and glassy. Five minutes later it was pouring rain and we were paddling into 3ft swells trying not to go backwards. It would have been a great downwinder if we were going the other way.

I battled on for a few minutes, quickly losing sight of the canoes as their lower profiles (and training) allowed them to plough on, before realising I was going so slow I might as well be standing on land. So I ignored Bart’s golden rule (“Don’t take a break on land.”) and beached myself.

Most of the SUPs got off the water during the storm as did several of the canoes and kayaks. One of the big voyageur canoes flipped and had to be rescued. It was a rough time for everyone on that damn lake, but the SUPs definitely had the worst of it whenever there was headwind.

Standing alone on a remote shore, huddled in my heavy-duty rain jacket (I suddenly wanted to hug the race official who forced me to bring it) and trying to take refuge under the trees without straying too far into bear country, I suddenly realised my race was in trouble.

Every calculation I’d made for the cut-off times was based on getting a free ride across the lake behind one of the canoes (“Make sure you buddy up on the lake,” was Bart’s advice). But there was no way I could draft in these conditions, and if the wind didn’t die I’d be lucky to manage 3km/h on my own. There was still 45km of lake to cover and only eight hours to cover it.

We were only five hours into a three-day race and I was already struggling. What on earth had I signed up for?

I finally cracked a smile after Lake Laberge started to calm down (photo: @perfectnegatives/@paddleleague)

Fortunately the wind and rain started waning after 30 minutes and I was back on the water, but for the next two hours we paddled into leftover chop that had been whipped up in the distant corners of the lake.

Halfway across and feeling like I was already at the back of the field, Lake Laberge returned to her calm ways and there was suddenly a glimmer of hope that I’d make the “Lower Laberge” cut-off before it closed at 1am. Towards the end of the Lake we even had a few little downwind bumps after the wind mysteriously picked up again (in the opposite direction, thank god) late in the evening.

It was here that I made some quick, on-the-spot alterations to my long sleeve compression top and turned the right arm into a quasi-glove, which finally gave my already-blistered hand some respite.

Note to self: Don’t sprint next year.

I eventually hit Lower Laberge 17 minutes after midnight, 43 minutes inside the cut-off bubble. We didn’t have to stop at this checkpoint, just shout our number and keep paddling. But many teams did, myself included, and we used it as a chance to change clothes, share horror stories about the lake and warm up for the graveyard shift ahead.

I jumped back on my board just before 1am and headed off into the hazy twilight of the never-night. This is the “Race to the Midnight Sun,” and although it does eventually set, the darkest it ever gets is an eerie sort of dusk between 1am and 3am. The days literally never end.

The next 30km felt like a ghost ride at the local theme park.

The light faded just enough to make shadows dance (aided by my weariness), and the sudden speed of the river (up to 10km/h in some places) compared to the motionlessness of the lake created a rollercoaster effect. I was also entirely alone, which only added to the mystique.

The golden glow of the Lower Laberge checkpoint (photo: @wheresbossman)

It was about 4am Thursday when I realised two damning facts: While the sun had surely risen (it was broad daylight) it still hadn’t appeared above the steep mountaintops to bathe us in its glorious warmth. And I couldn’t feel my feet.

I’d been paddling in zombie mode and couldn’t remember the last time I felt my toes, so when I reached the next checkpoint – again, not a mandatory stop but a definite refuge for the weary – I spotted a campfire and immediately pulled over.

Within a minute of getting off the water and standing still, chills were shooting through every part of my body. Hypothermia was creeping up on me fast and I knew my race would be over if I didn’t warm up immediately.

It would take an hour of sitting next to that remote campfire (very few checkpoints have road access) drinking hot chocolate and wrapped in a beanie & blanket before I felt confident of returning to the water. The poor Frenchman beside me had already been there for two and was still shivering. One of the last canoe paddlers limped in to join us but couldn’t even hold his cup he was shaking so bad.

Apparently that first night was a cold one even by Yukon summer standards. Several teams withdrew due to hypothermia. I entertained the idea of retiring and curling up into my sleeping bag – every few kilometres we’d pass a perfect camping spot along the river that teased us with its wild coziness – but I also remembered just how many people I’d told about this race that were following my GPS tracker online. I kept paddling for them, not me.

At this point I presumed I had to be the last paddler in the field. I’d only seen one SUP pass me in the “night” and knew there were four more way out in front, so of the 10 of us that started I figured 4 had already quit or missed the cut-off.

The next part of my Quest was a total haze.

It’s difficult getting back on the water at 4am when you’re cold, when you’re tired, when you’ve been paddling 16 hours straight and still have another 18 til the main break.

I made it to lunchtime before I simply had to stop. My paddle strokes had become taps of the surface and I’d started falling asleep standing up. I also knew there was another 90km to the oasis of the Carmacks rest area.

Spotting a small, rocky outpost in the middle of the river (I figured there’d be less bugs away from the shore), I pulled over and lay down on warm stones under the midday sun for the sweetest and most uncomfortable 10-minute sleep I’ve ever had.

It’s amazing how much energy you can gain from a quick rest. Bart de Zwart told me about his strategy of taking 30-second mini-sleeps while crouched on his board. I almost felt guilty for taking a full 10 minutes.

Refreshed and mildly energised, I hit the river and soon had company — looking over my shoulder I realised I wasn’t the last paddler.

First came a pair of C2 teams that provided my first human contact in eight hours and a buzz of energy. Just talking can keep you awake. Then I spotted a couple of figures that appeared to be standing in their canoes. I was sure the other SUP teams had long since scratched, but sure enough it was the British “SUP Soldiers” Mike Procter and Ben Ashwell slowly closing in on me. They’d scraped through the earlier cut-offs and were paddling like metronomes towards Carmacks.

The duo had initially been joined by a third soldier, Stuart Croxford, but he lost touch shortly before the group caught me and would eventually withdraw after 30 hours. Stu had a pretty good reason: he lost a leg after an explosion in Afghanistan and was paddling with a prosthetic, which was giving him all sorts of problems. He battled on but succumbed to the mighty Yukon, determined to return in the future and complete his Quest.

All three of the soldiers were paddling 13ft inflatables, which was downright heroic and probably more than a little naive. Mike told me this was their first serious race. I replied that most people start with a 3km open event. These boys had jumped in the deep end…

I’d later find out that the 10th stand up paddler, Emily Matthews, had withdrawn at the lake after narrowly missing the cut-off. Emily had nothing to prove though: she’s already completed the Quest twice and only finished a round of chemotherapy three months ago. The fact she even started this year was incredible.

The Yukon River Quest is traditionally a canoe race (photo: @perfectnegatives/@paddleleague)

As the effects of sleep deprivation started to take hold, Ben, Mike and I paddled home to the rest stop as a trio. We were dazed, we were tired and we were sick to death of seeing endless pine trees. The Yukon is incredibly beautiful but a little variety in terms of flora couldn’t hurt.

Arriving in Carmacks, the first of two mandatory rest stops but the only one with team support, I was in shock. It had been 33 hours and 37 minutes since the Quest began. Suddenly, standing on solid ground felt strange. Having slept for 10 minutes in 40 hours felt strange. Having paddled all day, all night and all day again felt really strange.

I stood there, stunned, not really knowing what to do as my crew tried to convince me to eat, shower and go to bed. I was so tired I was actually getting annoyed at people giving me directions, but soon realised they knew better and heeded their advice.

It was at this point I realised just how important a good support team is. This race is technically possible without one but would be pretty damn tough. It’s not just the physical support – lifting your board out of the water, having a tent ready for you to crawl into, refilling your water packs – it’s the emotional relief. Just getting a hug can lift your spirits no end.

I would later find out my support crew slept even less than me during the race. All I had to do was paddle. I had the easy job.

I awoke at 4am Friday feeling a million dollars. I’d only slept five hours and still hadn’t caught up on the previous night, but it didn’t matter. I knew I could finish from here.

I crawled out of my tent and made sure I had enough food for the 400+ kilometres and 35+ hours of paddling in front of me. The team filled up my water packs and carried my 35kg board down to the water.

It also occurred to me that being a backmarker has its advantages. We’d been off the water in Carmacks between 10pm and 5am (it’s a mandatory 7-hour break), which is almost a normal night’s sleep. The faster paddlers had arrived at lunchtime, slept all afternoon then woken up in the evening and paddled all through the night again. Murder.

Morning face; 4am Friday (photo: @perfectnegatives/@paddleleague)

Friday morning flew by.

I was in a trance. I didn’t want to look at my clock for fear of making time stand still, but after what I’d assumed was 30 or maybe 45 minutes of paddling, I snuck a look.

I was instantly confused.

My clock said 9am, which would have put me on the water four hours already. Impossible. I figured my phone had glitched out and changed timezones, so I asked a passing canoe team and they confirmed I had indeed left this world for the past three and a half hours.

Where exactly I went in that time I still don’t know, but fortunately my body had remained on the river and kept paddling on autopilot.

The river has a habit of doing that. It bends your mind and distorts your spatial reality. Sometimes you’ll think deep thoughts, sometimes you’ll think no thoughts and sometimes you’ll just hallucinate.

The Yukon is famous for its tales of delirium: Lina Augaitis was convinced she’d seen dead bodies floating in the river in 2016. Most paddlers will see perfectly-formed faces in the rocky outcrops. Everyone hears voices at least once or twice.

I saw an Indian chief.

He was there on every island during the twilight hours, and there are hundreds of small islands in the Yukon River. The chief sat calmly in his chair, hands by his side. I could clearly make out his black hair and crown of feathers. He sat motionless but those eyes always followed me. I couldn’t tell if he was looking out for us or looking for us. We were paddling through the lands of the “First Nations” after all (Canada’s indigenous people) and I feared I’d angered the locals.

The face of delirium; “waking up” 5am Saturday at the ironically-named Coffee Creek (photo: @wheresbossman)

By Friday afternoon things were still on track. I’d met up with Mike and Ben and we’d calculated an arrival of around 12.30am at Coffee Creek, the second mandatory rest stop where we’d be off the water for 3 hours and hopefully catch up on a little sleep before the final 170km stretch to the finish line in Dawson. We were 2 or 3 hours ahead of schedule and I even naively flirted with the idea of taking an extra hour’s rest.

Then the wind came up. Again.

For the third afternoon in a row we experienced headwind, and this gale was the worst one yet. The surrounding mountains acted like a funnel, and despite the river winding in every direction the wind was always in our face. We were in the world’s largest wind tunnel going the wrong way.

The headwind destroyed my pace and almost broke my heart. I was on my knees trying to keep a respectable rhythm, but all we could do was stop ourselves going virtually backwards and stay with the river flow.

I couldn’t even keep up with Mike and Ben on their inflatables, and they could barely keep pace with a stick that was floating out of the wind at the same speed as the river (“For 15 minutes I tried to pass that damn stick”). If it wasn’t for the flow of the river, we literally would’ve been standing still for five hours.

We limped into the ultra-remote outpost of Coffee Creek (no road access, no support teams) at 2.37am Saturday, completely exhausted and now in serious danger of missing the final cut-off time of 9pm in Dawson that evening.

But I hadn’t come this far and trained this little to miss out on finishing a three-day race by five minutes, so we jumped in our sleeping bags and tried to switch off.

We didn’t sleep much at all.

Between having to sleep on the ground (literally) and fighting off a horde of midsummer mosquitoes, I probably got 30 minutes of energy-boosting rest during that mandatory three hour break. We didn’t have a minute to spare though, so 30 would have to do.

As we stumbled back to the shore around 5.30am, thankfully not a breath of wind in the early morning air, we ran the numbers to calculate a required speed of 11.3km an hour, which we’d have to hold for the next 15 and a half hours…

But I didn’t want to risk it: I hammered off at 13km/h to get ahead of the invisible wall that was chasing us. There actually was a sweeper boat chasing us, but to me it felt like something far greater was on my tail.

I eventually convinced myself that I was being chased by the Midnight Sun itself, as if this giant orb of energy was rising over the mountaintops each morning, bouncing down onto the river and silently floating along behind me. I could see it, I could feel it, and at more than one point I wanted to stop, quit the damn race and be engulfed by its glorious warmth. It was the siren of the Yukon.

There was still 12 hours of paddling and I was seriously starting to lose my grip on reality. As the hallucinations and delusions grew, I tried to regain my focus by opening a workout app with a voice coach that would shout out my average speed. I set her volume to max and interval to 60 seconds, and I proceeded to get about 720x updates from this robotic woman’s voice over the next 12 hours informing me of my depressingly-slow velocity. At least she kept me awake.

Food was another issue for me.

The conventional wisdom of this race says carry a lot of variety and carry things you’ll crave, because it’ll give you a mental boost when you’re struggling in addition to the raw fuel it provides. But apparently I don’t like food, because no matter how many nuts, fruits and M&Ms I had in front of me, I rarely felt like eating. Delicious chocolate suddenly tasted horrible. I didn’t want sugar, I didn’t want salt and my teeth felt like chalk. Fortunately I had some of my Saturo liquid meals, which kept me going, but for the most part I was way under my recommended calorie intake. This race would be a great scientific experiment.

The same went for water. I had to force myself to drink. It became a chore. I knew I was becoming dangerously-dehydrated but I simply didn’t care: I just didn’t want to drink anymore.

All of which meant my speed was gradually decreasing throughout that final day.

Fortunately the confluence of the White River gave the Yukon River a boost and a flow speed that briefly hit 14km/h. For a few kilometres it felt like we were paddling downhill. This was also where the terrain moved from luscious green mountains into barren, other-worldly moonscapes of dark sandy islands and spooky dead trees.

The sleep deprivation was already trying hard to convince me I was on another planet — this eerie landscape finished the job nicely.

Shortly after midday, the incomprehensible length of the Yukon River Quest could be summed up with my feeling of relief upon realising there was only another 100km to the finish; “100km is nothing,” I thought. Suddenly it felt like Dawson was around the next corner.

The final eight hours were an exercise in patience, focus and map-reading. If the Yukon is a story then one of its main characters is a map named “Rourke.”

Mike Rourke created the Yukon River bible in the 70s and its still regularly updated and used by canoeists today. It’s a maddeningly-simple map with basic outlines of islands and mountain slopes alongside bizarre acronyms and abbreviations that will take you days to decipher (OGRN CB slope with LP?). But it’s a priceless lifeline in the Yukon River Quest.

Not only does the Rourke map help you navigate a maze of islands and pick the fastest flow of the river – which itself is crucial because going the wrong way around even just one island can cost you several minutes as you hit dead water – it also keeps you focused.

Bart told me to literally take this race “one page at a time” and his advice was spot on. Each page of the Rourke map equates to about one hour of paddling, which is long enough to make some real progress but short enough to keep your mind occupied. Stu had also drawn a route map and told me which islands to avoid. That pen line became my lifeline.

The Rourke map, or “Rourkey” as I named him (if the race had gone any longer I probably would have gone full Tom Hanks and painted a Wilson-face on the cover), helped us close the gap on Dawson without completely losing our minds.

But we still made mistakes.

The river had morphed into a labyrinth of warped islands and identical-looking sand banks. At one point – dazed, confused and reading the wrong page of the map – I took a wrong turn and lost a good 20 minutes just trying to find my way back to the main river channel. It would have been frustrating on any normal day. After 65 hours it was downright maddening.

Following a fourth-straight afternoon of headwind, which allowed the final few canoe and kayak teams to pass us, Mike, Ben and I huddled together as the Midnight Sun sweeper boat sat ominously on our tails and the race clock ticked towards 70 hours. We’d hoped to reach Dawson in time for dinner but the headwind cut our margin of error down to zero.

The face of relief. (photo: @perfectnegatives/@paddleleague)

The clock struck 8:39pm as we reached the small dock in the small town of Dawson on Saturday evening. We were the last three paddlers off the water, though considering more than a quarter of the teams had withdrawn we didn’t feel like we were last.

A small crowd of supporters, volunteers and all of the stand up paddlers cheered us home.

As I hit land and tried to walk, I couldn’t. My ankles were so swollen and soles so shriveled that I could barely stand. But despite looking like death and sporting a zinc-smeared face resembling an Aboriginal painting, the only feeling I had was one of relief. I hadn’t set out to finish the Yukon River Quest in record time, I’d simply set out to finish.

70 hours, 39 minutes and 13 seconds was my official time. The cut-off was 71 hours.

I didn’t train for this race. I signed up late and figured it was more of a mental challenge than a physical one, so I’d convinced myself I could just push my mind through it. I was half right, but I underestimated how tough it would really be, and I totally underestimated how much I’d rely on others.

The other thing that struck me, apart from the value of support (and the misery of headwind), was the energy of camaraderie.

Stand up paddling is known to be a tight community but on the edge of the world those bonds are enhanced. We were all full of support for each other, and the fact everyone withstood the overwhelming urge to sleep and waited for the three musketeers to finish summed it up perfectly.

Bart had been waiting there all day. He crossed in a time of 56 hours. It was a record slow year for everyone with the headwind and relatively low water level — even Bart was three hours outside his best time — but he still safely secured his fourth title and cemented “legend” status in the ultra-paddling world.

Peter Allen aka @sup_n_irish finished runner-up just two and a half hours behind the champ. It was a very impressive performance — Peter will probably win this race one day.

Shauna Magowan claimed the women’s title with a fantastic time of 62 hours, which put her third overall. Her spirit on and off the river was downright inspiring. Shauna lost a loved one to cancer last year and wanted to complete this race to overcome her fears. She didn’t just complete it, she conquered it.

Brad Friesen came home in 66 hours. He was inspired to enter this race after randomly spotting Bart paddling the Yukon 1000 during a family camping trip last year. He would later tell us his motivation for finishing was to show his four-year-old son that tough things can be done with perseverance. It was fascinating to hear everyone’s “reason why” in the post-race debrief.

Ben Ashwell and Mike Procter hit the line beside me. The fact they finished at all on those touring inflatables was rather extraordinary.

The legend himself: Bart de Zwart (photo: @perfectnegatives/@paddleleague)

The Yukon River Quest probably isn’t for everyone but I’d recommend it to anyone. Some would find it too difficult, some too boring, while many would question “why?” anyone would subject themselves to such mental and physical torture in the first place.

It certainly wasn’t easy, but I found the whole experience to be rather incredible. It’s made me appreciate paddling again, among many other things.

I’ve always wanted to do the Yukon race but never knew why, so I suppose my ultimate motivation was to simply find out why.

There was of course the raw element of adventure and desire to share the story of this epic event with the paddling world. But in the end, as straightforward as it sounds, I realised I did the Yukon River Quest just to prove to myself I was mentally strong enough to do it. Great things can be done when you simply decide they’re going to be done.

I knew I wouldn’t be setting records but I never seriously considered not making it. And I may not have taken my preparation seriously, but from the moment I was committed in my mind I was committed. Nothing was going to stop me finishing. Not a cut-off time, not a sweeper boat, not a mysterious Indian chief.

I also found a beautiful sort of contentment somewhere out there on that lonely river. It can be a surreal, almost-spiritual experience. “Reconnecting with nature” sounds a little clichéd, but I didn’t have internet on my phone for four days straight and was in the middle of nowhere surrounded by natural beauty. It was exhausting but utterly refreshing.

Whether it’s enjoying the tranquility of nature, taking an unexpected mind trip (who needs mushrooms?) or simply pushing yourself so far out of your comfort zone that you’re forced to learn what you’re really made of, these ultra-endurance races are stunningly-addictive.

Left-right: me, Ben, Mike, Peter, Shauna, Bart, Brad, Stu (photo: @trev_sup/@paddleleague)

Quest complete, the only thing left was the infamous “toe shot” at the local bar.

Dawson was the centre of the Klondike Gold Rush over a hundred years ago and by 1898 housed 40,000 people. Today, the official population is 1,375. It’s called “Dawson City” but even “town” would be generous.

I loved it.

The streets are still made from dirt and the buildings from old wood. I felt like I was stepping onto the set of Westworld. But with the gold rush having long since peaked, Dawson is now famous for something else entirely: a human toe.

The origins of this story are vague but the ritual is clear: visitors to Dawson can buy a shot of booze and have a mummified toe placed in it. It’s not just a drink, it’s a performance. The master of ceremonies (a 90-year-old man named the “Captain”) tells you that “You can drink it fast, you can drink it slow, but your lips must touch the toe,” before dropping an actual human toe in your shot glass.

It all sounds incredibly bizarre. But I suppose after having just paddled 715 kilometres down a cold river on a stand up paddleboard, drinking a human toe is a perfectly normal thing to do.

There are too many people to thank, but those who I remember: Stuart Knaack from SUP Yukon for providing me with virtually everything including a board, gear, river knowledge, a place in the event and a place to stay. Kelli and Trevor who stayed up all day and all night shooting awesome photos and video. Starboard who funded most of this trip so we can produce our documentary along with great support from Quickblade Paddles and VMG Blades. Peter Coates, Jeff Brady and all the other organisers from the Yukon River Quest who welcomed us to the event and put in a superhuman effort to pull off the most logistically-maddening race imaginable. The scores of volunteers who made the race possible, made our lives easier and greeted us at the rest stops with a Mexican wave. The people of the First Nations who let us paddle through their lands. Ben and Mike for giving me much needed company on the water and ensuring I didn’t lose my mind or quit the race. Kalin who lent me his GPS tracker at the last minute when I was at serious risk of being denied a spot on the start line. Liz from Ontario for ensuring our support team was looked after in Carmacks. Chris from Calgary for being a great board caddy. Spencer from Yukon Wide Adventures (2018 champs and 2019 runners-up) who championed our request to join the event. The Aussie boys Steve-o and Big Fizz (“How are we?”) that kept us entertained before, during and after the race with their laidback antics. The horsefly that violently attacked me on day two and actually did a good job of keeping me awake. The Captain for letting me touch his toe. The always-supportive Shauna, Peter, Brad and Stu for sharing the adventure and waiting patiently at the finish line. My family for remotely supporting me all week (and always). And finally, Bart de Zwart for inspiring me (and many others) to do these kinds of races and for giving up so much of his time and knowledge to support the sport of ultra-endurance paddling. You’re a legend, mate.

The Race to the Midnight Sun…

You must be logged in to post a comment.